Exploring Gender Pronoun Distribution and Character Identification in 19th Century Novels

Cormac Dacker, Tyler Gomez Riddick, Avery Pike

Introduction

ad

ad

Personal pronouns are a critical element of language that can provide insights into character portrayal and gender representation in literature. This study investigates two primary questions:

- Is there a statistically significant difference between the frequencies of subject and object pronouns for feminine and masculine personal pronouns?

- Is it possible to predict the gender of a character in a story using the pronouns associated with them?

To address these questions, we analyze subjective pronouns (he, she) and objective pronouns (him, her). While “him” is straightforward to identify as an objective pronoun, “her” can be either an objective pronoun or a possessive adjective. To distinguish between these usages, we implemented a function for part-of-speech (POS) tagging that identifies instances of “her” not followed by a noun (NN or NNS type) as objective, and the rest as possessive. We also considered possessive adjectives (his, her) and possessive pronouns (his, hers), treating “his” as both an adjective and a pronoun for simplicity.

Methodology

Datasets

We used the following literary works from Calvin’s Project Gutenberg repository:

- Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

- Frankenstein: Or, the Modern Prometheus by Mary Shelley

- Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë

Technologies

We utilized SparkNLP for POS-tagging and Spacy for Named-Entity Recognition (NER).

Process

- Corpus Preparation: Identified the corpus of interest and cleaned the text by removing periods after honorifics and hyphens.

- Text Processing: Reinserted periods to facilitate the identification of objective “her.” This ensured possessive adjectives “her” followed by nouns were correctly identified.

- Pronoun Counting: Counted instances of male and female pronouns in each sentence, associating counts with character names in a dictionary.

- Dictionary Conversion: Converted the dictionary to a list for iteration and further processing.

- Character Filtering: Excluded characters with fewer than 10 pronoun occurrences to focus on significant data points.

- Gender Prediction: Predicted the gender of each character based on pronoun counts.

- Manual Verification: The function “manually_verify” allowed manual verification of character gender, enhancing the accuracy of predictions.

- Accuracy Calculation: Compared true and predicted values to determine accuracy, including total accuracy, male accuracy, and female accuracy.

Hypotheses

- Given that all books in the corpus are authored by women, we hypothesized no statistical difference between the counts of subjective male pronouns, subjective female pronouns, objective male pronouns, and objective female pronouns.

- We hypothesized that gender prediction based on pronoun counts in relevant sentences would be more accurate than a random guess.

Evaluation

Character Gender Prediction

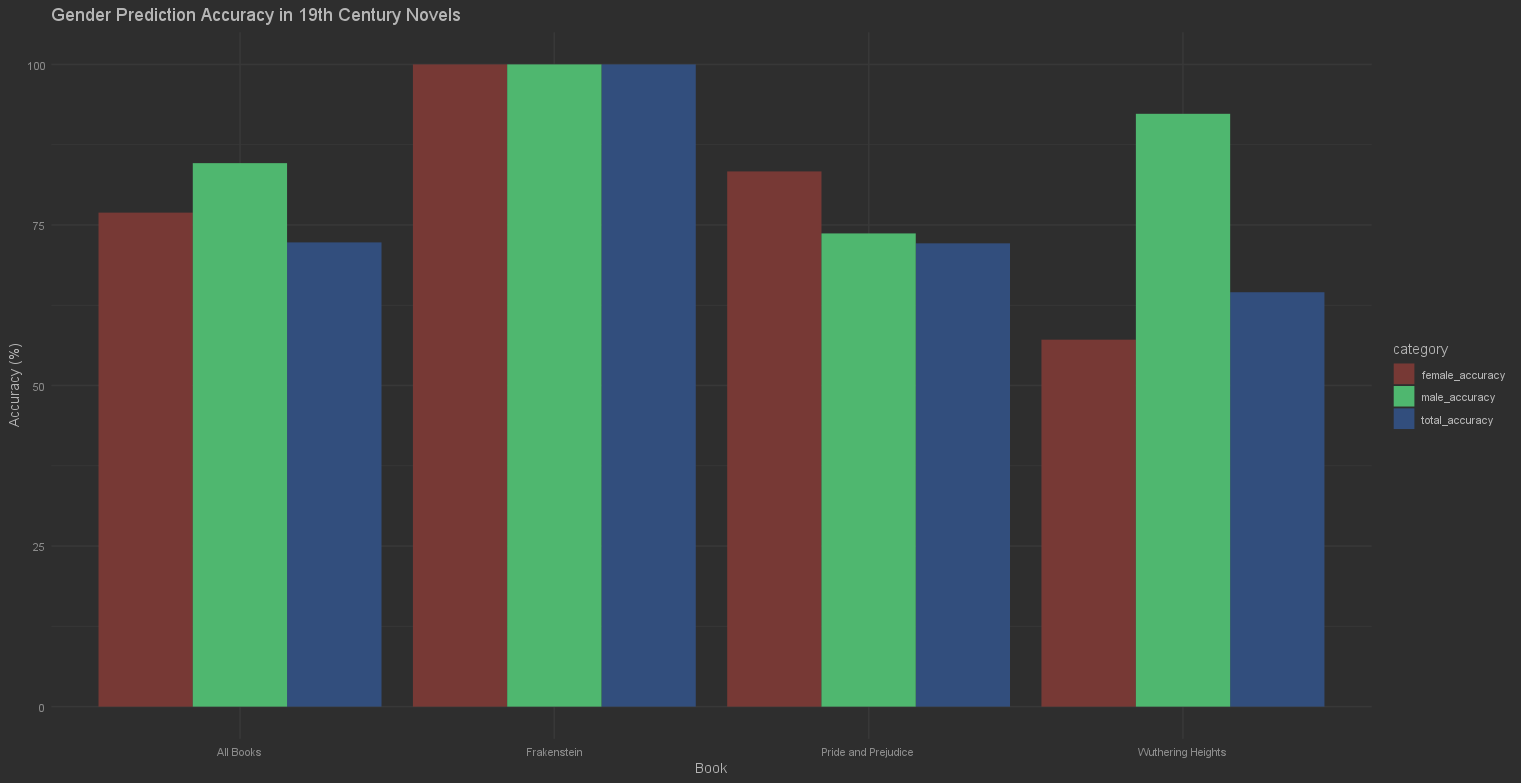

Accuracy was calculated by dividing the number of correct predictions by the total number of predictions. Results were split by book to evaluate model performance across different texts. We also measured accuracy by gender. Notably, Frankenstein achieved 100% accuracy, likely due to its smaller cast of characters. The above visualization shows the male, female, and total accuracy for each of the books and all the books together. We found that our model, for characters with more than 10 nearby pronouns, is more accurate than a coin flip in all cases for this corpus.

Pronoun Frequency Analysis

We conducted statistical tests to compare the frequencies of male and female subjective and objective pronouns. Our findings indicated no statistically significant differences between the frequencies of male and female subjective pronouns (p-value=0.74), nor between male and female objective pronouns (p=0.09). It is important to note that though neither of these results are statistically significant, the p-value is pretty close to the standard accepted threshold of 5%.

Conclusions and Future Research

Our initial hypothesis that a corpus of entirely women authors would lead to no difference between the frequency of pronouns for each gender was supported by our model. We also had success with our predictive accuracy of gender counts. The study supports the notion that the gender of the author affects not only the frequency of respective gender pronouns, but also predictive accuracy within the corpus. Further work can be done to expand the scope of pronoun detection, which may increase or decrease accuracy (though we predict it will improve accuracy).

This observation suggests the need for further research into pronoun usage concerning author gender. It would be irresponsible to suggest any concrete relationship between author gender and pronoun prediction accuracy from such a small corpus, but these initial findings and confirmation of our hypotheses are promising in suggesting that the gender of the author has significant influence on gender pronoun usage.

With confirmation from a larger corpus and appropriate comparative analysis with a corpus of male authors, there could be considerable real-world significance to the observations made from this study. Because most published materials in English have had male authorship, this could suggest that predictive models that do not consider the ratio of authorship between genders possess inherent bias against recognition of feminine pronouns. This point contributes to linguistic arguments that a lack of representation in the development of English has obfuscated feminine viewpoints, contributing to patriarchal ideological concepts such as the “Feminine Mystique.” By analyzing this corpus, this study suggests that there is validity in further research in this field.